The interactive character of installation art

Works of installation art are structured around the beholders, who are invited to explore their spaces and the objects possibly placed within those (see e.g. Reiss 1999; Rebentisch 2003; Bishop 2005; Ring Petersen 2015).

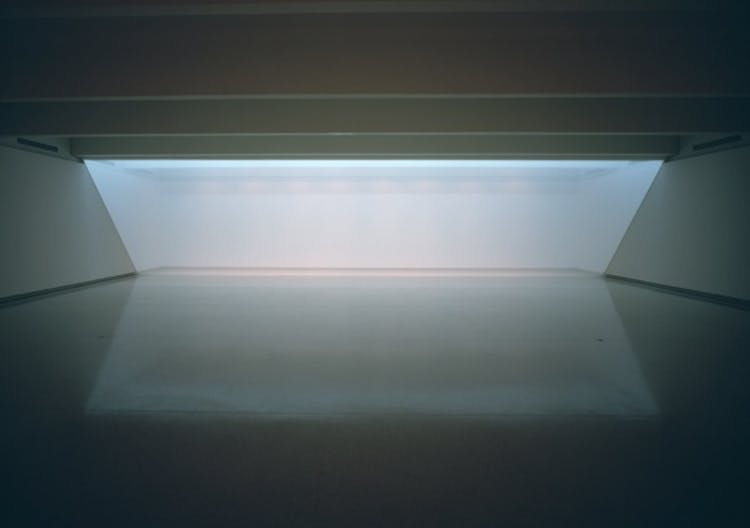

Think of Robert Irwin’s Untitled (1971). The work is displayed by hanging a rectangular, transparent cloth from the ceiling of an empty gallery room and anchoring it to the floor, to keep it stretched and wrinkleless. The cloth hangs obliquely – its lower rim is closer to the back wall of the room than its upper rim – and is as wide as the back wall: the beholders cannot reach the back wall, but they can get close to the cloth, which creates a space with a very sloping roof. The cloth is illuminated with fluorescent lights and its image is reflected by the polished, uniform gallery floor: as a consequence, when the beholders get closer to the cloth, they have the visual experience of entering into a luminous prism. The gallery floor, walls and ceiling are integral to the display of Irwin’s work, which is a simple, luminous space that the public is invited to enter and explore.

Robert Irwin, Untitled (1971)

Think, also, of Yayoi Kusama’s The Obliteration Room (2002), a much more complexly structured work which, at the beginning of its exhibition, shows an entirely white apartment, complete with white furniture. Here, the public is confronted with an articulated space and is invited to cover, or better yet, obliterate it with brightly coloured stickers, so that the apartment gets more and more colourful over the course of the work’s exhibition.

Irwin’s and Kusama’s works show that installation art can prompt the public to engage in various sets of actions. The actions prompted by Untitled are rather basic: one is invited to enter its empty space, walk, sit down, or perhaps even crawl, and undergo the visual experience aroused by the fluorescent lights. By contrast, the actions prompted by The Obliteration Room are more complex: one is invited to enter a furnished space and to put stickers over every available surface. Are works of installation art interactive?

Berys Gaut argues that “a work is interactive just in case it authorizes that its audience’s actions partly determine its instances and their features. So traditional musical and other performing works are not interactive, for the audience is not authorised to determine their instances and features; the performers do that. But in interactive works it is the audience that determines the work’s instances and their features” (Gaut 2010: 143). Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed plays, according to Gaut, are a case of interactive works: audience members who go on stage during the performances of the plays partly determine the works’ instances and their features. Do works of installation art fit this view of interactivity?

First, according to Gaut, interactive works are types whose instances are tokens, i.e. they are multiply instantiable works (2010: 141). If, with Sherri Irvin (2013; 2020 forthcoming), we argue that works of installation art, like other contemporary works of art, are non-physical historical individuals susceptible of having multiple occurrences (unless they have essential enduring physical components, in which case they are hybrid historical individuals with both physical and non-physical elements), then we can conclude that works of installation art are, too, multiply instantiable works. According to this view, any new exhibition of Untitled, for instance, is a new occurrence of the work (more on this below).

Second, Gaut (2010: 141) argues that only those among the audience’s actions that are authorized by the work’s author contribute to producing tokens of an interactive work. This, too, is in line with Irvin’s views of contemporary artworks – including works of installation art – (see 2020 forthcoming): she argues that various works of contemporary art are governed, among other things, by rules for participation, which establish what kinds of actions the public is allowed to perform when interacting with them. Kusama’s work, for instance, allows the public to put stickers around the room but not to, say, draw on its walls.

Finally, according to Gaut, interactive artworks are “types of which their interaction-instances are tokens” (Gaut 2010: 141), which means that the audience of those works contributes to producing their tokens (by performing authorized actions). Is this condition, too, satisfied by works of installation art?

Irvin does not discuss the hypothesis that the public participate into the instantiation of the displays of works of installation art, focussing instead exclusively on the role that art institutions play in producing the works’ displays. It seems, then, that according to Irvin the displays of e.g. The Obliteration Room are those produced by art institution teams whenever the work is exhibited.

An alternative view, according to which works of installation art fit entirely Gaut’s understanding of interactive art, is the following: art institution teams produce partial displays of works of installation art whenever the works are exhibited, while the works’ public completes the displays by interacting with them in the way sanctioned by the artists through the works’ rules for participation. In particular, display completion happens whenever a member of the public interacts with one of the partial displays of a work in the way sanctioned by the artist. Each partial display, then, can prompt the making of many complete displays.

To this proposal one could object that while it is evident that the public modifies the display of The Obliteration Room by putting stickers around the room, those who enter Untitled leave no trace of their actions and therefore don’t seem to contribute to the production of the work’s displays and properly interact with it. This objection, however, relies on a narrow understanding of what counts as the display of a work of installation art, which is not faithful to the practice of installation art.

In installation art, in general, members of the public, are “in some way regarded as integral to the completion of the work” (Reiss 1999: xiii). This aspect of installation art has been thoroughly investigated by Claire Bishop (2005), who has argued that we should regard all works of installation art as experimenting with the public’s experiences. Now, one could observe that this is what any artwork does, in a sense. I submit, however, that the lesson to learn from Bishop is that in installation art artists use the public’s experiences as material for their work, manipulating them to prompt the public to appreciate some qualities of those experiences, in the same way as a painter might experiment with oil paint to prompt the public to appreciate e.g. its expressive qualities. The public’s experiences, then, play a different role in installation art than e.g. in pictorial art: when we appreciate a painting, the obtaining of a certain visual experience is instrumental for us to be able to focus on the materials manipulated by the artists, such as oil paint and the configurations of marks and colours on a surface it allows to produce; however, the appreciation of the very fact that we have a certain visual experience while looking at the painting is not part of the experience of pictorial appreciation: the visual experience has a purely instrumental role. In installation art, instead, the experiences occurring as a consequence of the public’s interacting with the work’s partial displays in the ways prescribed by the artist are among the things the public is required to focus on, per se, in order to appreciate the work. This is why the public’s experiences contribute to completing the displays of a work of installation art, no matter whether the public’s interactions with the work’s partial display issue in publicly observable results. The public’s experiences, then, are part of the works’ displays.

According to Irvin (2020 forthcoming), works’ displays are public events during which the works’ audience encounters certain objects. I am sympathetic to this view, but I suggest an amendment for works of installation art: those works’ partial displays are public events during which the works’ audience encounters certain objects, while their complete displays are the sum of a public event during which the works’ audience encounters certain objects plus the private event of experiencing those objects. The private event, however, isn’t essentially private, because it can be described to other people and members of the public can compare the respective experiences of display-events.

Let’s consider again Irwin’s and Kusama’s works. To appreciate both it is crucial that we focus, among other things, on some of the qualities of the experiences they arouse in us.Untitled’s goal has been described as the exploration of “how phenomena are perceived and altered by consciousness” and Irwin’s activity as “in effect orchestrating the act of perception” (Irwin, Slant/Light/Volume; see also Irwin 1985). Bishop writes about Irwin (as well as other ‘West coast’ artists like James Turrell): “The phrase ’light and space’ was coined to characterise the predilection of these artists for empty interiors in which the viewer’s perception of contingent sensory phenomena (sunlight, sound, temperature) became the content of the work” (Bishop 2005: 56, my italics).

As for Kusama, in her early years she used to experience hallucinations, some of which of polka dots, and she has produced a significant body of work about self-obliteration (e.g. Dots Obsession, 1998) where she appears covered in polka dots to blend in a similarly looking environment (see Turner 1999). The Obliteration Room, then, can be described as orchestrating for the public an experience similar to those had by the artist.

This text is a slightly modified excerpt from my essay “On Experiencing Installation Art”, forthcoming on The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism.

Elisa Caldarola is a Research Fellow at the Philosophy Division of the FISPPA Department of the University of Padova, Italy, and Principal Investigator for the research project “A Philosophy of Art Installation” (2018-2020).

References

- Bishop, Claire 2005. Installation Art. London: Tate Publishers.

- Gaut, Berys 2010. A Philosophy of Cinematic Art. Cambridge University Press.

- Irvin, Sherri 2013. “A Shared Ontology: Installation Art and Performance.” In Art and Abstract Objects, edited by Christy Mag Uidhir, 242–262. Oxford University Press.

- Irvin, Sherri 2020 forthcoming. Immaterial_: The Rules of Contemporary Art_. Oxford University Press.

- Irwin, Robert 1985. Being and Circumstance. Larkspur Landing: Lapis.

- Kania, Andrew 2018. “Why Gamers Are Not Performers.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 76: 187–199.

- Rebentisch, Juliane 2003. Aesthetics of Installation Art, translated by Daniel Hendrickson and Gerrit Jackson. Sternberg 2012.

- Reiss, Julie H.1999. From Margin to Center: The Spaces of Installation Art. MIT Press.

- Ring Petersen, Anne 2015. Installation Art. Between Image and Stage, Tusculanum Press.

- Rohrbaugh, Guy 2003. “Artworks as Historical Individuals.” European Journal of Philosophy 11: 177–205.

- Smith, Barry 2008. “Searle and De Soto: The New Ontology of the Social World.” In The Mystery of Capital and the Construction of Social Reality, edited by Barry Smith, David Mark and Isaac Ehrlich, 35–51. Chicago: Open Court.

- Turner, Grady 1999. “Yayoi Kusama by Grady Turner.” BOMB 66 Winter 1999: 62–69.