Beauty. Some Reflections on the Broad/Narrow Distinction

In this post I'd like to bring up for discussion some thoughts on the distinction between a so-called narrow sense of beauty—a specific quality or value—and a broad one—comprising aesthetic value or positive aesthetic qualities in general. This distinction is often acknowledged in contemporary analytic aesthetics, but rarely examined. I think that it's an important distinction, partly because it encapsulates some key tensions in modern aesthetics, and partly because it's a good starting point on which to start thinking about how to build a theory of beauty. At the same time, however, as presently drawn, it is also somewhat uninformative, and so potentially misleading. It is for this reason perhaps that, more recently, some have questioned the distinction and its usefulness. I will try to explain why we should avoid this move, and invite suggestions as to what should be done to replace, or refine the distinction in question.

The Distinction

Here's a typical formulation of the distinction, drawn by appeal to artistic examples, from the late Roger Scruton:

There is no contradiction in saying that Bartók's score for The Miraculous Mandarin is harsh, rebarbative, even ugly, and at the same time praising the work as one of the triumphs of early modern music. Its aesthetic virtues are of a different order from those of Fauré's Pavane, which aims only to be exquisitely beautiful, and succeeds.

Another way of putting the point is to distinguish two concepts of beauty. In one sense 'beauty' means aesthetic success, in another sense it means only a certain kind of aesthetic success. (2007: 15-16)

The distinction is found in the work of many others who write on beauty, including Jerry Levinson (2011) and Berys Gaut, who interestingly carves the distinction somewhat differently, at the level of the aesthetic, speaking of a narrow sense of the aesthetic, which relates to the beautiful, and a broad one, which relates to a "surprisingly heterogeneous set of properties", including properties like "unity and balance … serenity and sombreness; … being exciting and deeply moving; and … being trite." (2007: 27)

Those who draw the broad/narrow distinction also tend to converge on the claim that beauty in the narrow sense is "plausibly … essentially related to pleasure" (Gaut 2007: 29n; cf. Scruton 2007: 5; Levinson 2011: 191), but that this is not true of the broad sense; at least not in an equally straightforward way.

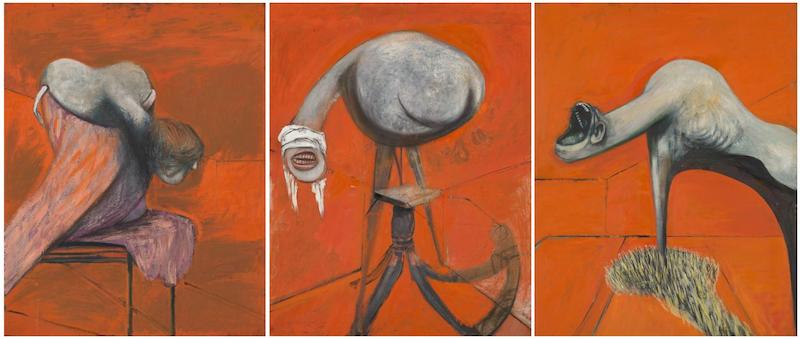

Francis Bacon, ‘Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion’ (1944)

Francis Bacon, ‘Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion’ (1944)

This brief survey, then, suggests a couple of things. First, there seems to be agreement about the sort of quality being delineated, and the distinction is taken to be pretty intuitive and straightforward—you just get it after a couple of examples. Second, the use of examples in drawing the distinction is noteworthy. For instance, it seems pretty clear to me that there's a sense in which Cezanne's Bathers is beautiful, whereas Bacon's Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion isn't.In other words, examples can do quite a bit of the heavy lifting here. Although it can be misleading, this, I think, tends to be good news for a distinction, especially in aesthetics. Finally, all three appeal to pleasure in elaborating the narrow sense of beauty. That's not much, but it's something. For if true, the capacity to arouse pleasure (presumably under certain specified conditions) can serve as a differentia for beauty in the narrow sense.

Rejecting the Distinction

Recently, however, a number of philosophers have rejected the distinction, either explicitly, or by hedging, presumably thinking it's more liable to mislead than help. Notably, Parsons and Carlson in developing their account of 'functional beauty' specify that by 'beauty' they mean "aesthetic appeal in general" (2008: xiii). Nehamas points out that people tend to think that beauty is distinct from aesthetic value more broadly due to a misconception on which the former requires no knowledge or understanding of the object but the latter does (2007: 43-44), a view which he goes on to reject. And Dom Lopes implicitly rejects the distinction when he asserts, albeit in a parenthesis, that ""beauty" [is the] (same thing) [as] "aesthetic value"" (2018: 1). However, he later addresses the distinction more explicitly and appears to not think very highly of beauty in the narrow sense. He writes: "Beautification happens, but only sometimes, and it is inevitable only if there is no beauty in the broad sense" (6), that is, aesthetic value in general. Other remarks suggest that the problem with beauty in the narrow sense is that it is "shallow, easy, sensuous" (6).

In all three cases, however, my impression is that what is gained dialectically in the respective accounts by simply shrugging the distinction off, is lost in philosophical understanding. Parsons and Carlson focus on form and function and speak of aesthetic appeal, form and pleasure being traditionally associated with the narrow sense of beauty, but deflect objections to their account by appealing to the broad sense of beauty (see my 2019a). Nehamas (2007) too appeals to a traditional network of concepts linking beauty, love, and happiness, which, I think, philosophers and laypersons alike would more readily associate with the narrow sense of beauty. However, he then applies his account to art and aesthetic value in general, including to artworks that may have seemed, and may still be thought of as, ugly, or at least not beautiful. Yet to do so, he basically suggests that these are, in fact, experienced as beautiful. Finally, Lopes (2018), by talking of beauty, recruits our intuitions to the appeal of hedonism, or at least views whereby pleasure is somehow necessary for beauty—most, if not all, of which stem from our thinking about the narrow sense of beauty and the aesthetic—and then criticises that view by using intuitions more closely associated to the broad sense, arguing that pleasure is too narrow a response to the breadth of the aesthetically valuable.

Now, on these accounts, beauty in the narrow sense is not only associated with pleasure, but seems to be conceived as a remarkably narrow notion associated with shallowness, superficiality, and easy pleasure or gratification. This is not surprising in the case of Nehamas (2007) and Lopes (2018) in particular, since they are reacting to the well-known rejection of beauty in modern art. But the way they do so, is by accepting the charge as it's levelled against beauty in the narrow sense, and seeking to escape it by appeal to the broad sense. That seems to me the wrong way to go because I think it's clear that while the contemporary conception of beauty, particularly human beauty, may be superficial and sensuous (cf. Widdows 2018), this does not mean that beauty need be all these things. One need only look at a work like Rembrandt's Jewish Bride to see this. For I think it's clear that there's beauty here, in a narrow sense, but that it's not shallow, easy, or superficial. Of course, it may well be that our culture's dominant conception of beauty has been becoming increasingly superficial ever since the invention of photography (Richards 2016), but it wasn't always so, and it needn't be so. Plato thought that beauty has the power to arouse love and through it make us good and wise. It's unlikely that by this he meant aesthetic value in general. After all, he probably wasn't thinking of humour, wit, or haunting qualities as the great redeemers—aesthetically valuable though these may be.

Rembrandt, ‘The Jewish Bride’ (1665-1669)

Rembrandt, ‘The Jewish Bride’ (1665-1669)

Some Reflections on the Distinction

As we have already seen, the only thing on which those who draw the broad/narrow distinction seem to agree on, is that pleasure plays a central role in the narrow sense of beauty. In some ways, however, that's precisely the problem for those who seek to evade the distinction. Lopes, for instance, seeks to dispel the view that beauty is "shallow, sensuous, and easy". In doing so, among other things, he appeals to examples like the beauty of mathematics. This is a perfectly effective move, sufficient to vindicate beauty in the narrow sense from the charge of shallowness etc., analogous with my appeal to the Rembrandt painting. But then Lopes proceeds to throw out the baby with the bathwater. He rejects a necessary link between beauty and pleasure, and takes mathematical beauty and other less sensuous kinds of beauty as instances of beauty in the broad sense (the "okay kind of beauty" (5), as he calls it). This seems to me a mistake: mathematical beauty seems a bona fide example of beauty in the narrow sense, and that becomes abundantly clear from mathematicians' own testimonies (e.g., Hardy 1991), as well as from the importance that pleasure seems to play in judgements of mathematical beauty (cf. Inglis & Aberdeen 2014 and my discussion in 2019a). Indeed, similar considerations hold for moral beauty (see my 2018a; 2018b, 2019b).

If this is right, then it looks like attempts to undermine the distinction between a broad and a narrow sense of beauty tread on ambiguities between particular conceptions of beauty or kinds of beauty, and a true, or at least plausible and potentially more pluralistic, account. But it's not hard to see why Lopes and others might seek to subvert the broad/narrow distinction. After all, that true account of beauty is still frustratingly out of our reach, and since our culture appears to identify beauty with superficiality and 'mere' appearances, advocating for a more intellectually-, less pleasure-based, more reason-responsive, is a natural recourse for philosophers who seek to safeguard the importance of beauty. But this doesn't mean it's a good idea…

So where does this leave us? On the one hand, it looks like there's an intuitive distinction to be drawn, and examples serve very well to draw it. Goya's Disasters of War series, for instance, is aesthetically valuable but not beautiful. This way of talking is common, taps into experience, and we had better produce some good grounds before rejecting it. A rejection of pleasure as the central component of aesthetic value in general, unless we presuppose that beauty just is aesthetic value, is not a good ground. On the other hand, the rejection of beauty in modern art, and the move away from beauty in modern aesthetics, has left us with an impoverished view of beauty (in the narrow sense).

Francisco Goya, from the series ‘Disasters of War’ (1810-1820)

Francisco Goya, from the series ‘Disasters of War’ (1810-1820)

So what should we do? Well, I suggest it might be time to turn our attention back on that most elusive, but pervasive property—beauty in the narrow sense—and examine it in its own right. And, as I hope to have illustrated, fraught as it is with some common disagreements and misconceptions in aesthetics,the broad/narrow distinction seems as good a starting point as any. However, we should proceed with caution, resisting, for instance, any straightforward identification of beauty with a specific conception of beauty—especially one on which beauty turns out to be one of the seemingly least important aesthetic qualities! Moreover, we should be wary of drawing the broad/narrow distinction too rigidly until we have a better grasp of what beauty is and how it can relate to other aesthetic qualities. This includes being open to the possibility that there are more distinctions to be drawn (I, for one, think that there's a distinction that may seem counterintuitive to many, between the appearance of beauty and genuine beauty). Finally, we need to be alive to beauty ourselves, open to expert testimony in fields outwith our expertise, and sensitive to how particular conceptions of beauty shape and are shaped by cultural factors (cf. Richards 2017; Taylor 2016); this leaves open the question of whether beauty is easy, shallow, and sensuous, or if it's the culture wherein such a conception of beauty can thrive that prizes superficiality and sensuousness (cf. Higgins 1998; Widdows 2018).

Thank you for reading this blog post—I'm looking forward to discussing your thoughts on these reflections!

References

- G.H. Hardy, A Mathematicians Apology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Kathleen M. Higgins, "Beauty and Its Kitsch Competitors", in Peg Zeglin Brand (ed.), Beauty Matters (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000), pp. 87-111.

- Matthew Inglis and Andrew Aberdein, "Beauty is Not Simplicity: An Analysis of Mathematicians' Proof Appraisals", Philosophia Mathematica 23:1 (2015), pp. 87–109.

- Jerrold Levinson, "Beauty is Not One: The Irreducible Variety of Visual Beauty", in Elisabeth Schellekens and Peter Goldie (eds.), The Aesthetic Mind(Oxford:OUP, 2011), pp. 190-207.

- Dominic McIver Lopes, Being for Beauty (Oxford: OUP, 2018).

- Alexander Nehamas, Only a Promise of Happiness: The Place of Beauty in a World of Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007).

- Panos Paris, "The Empirical Case for Moral Beauty", Australasian Journal of Philosophy 96:4 (2018a), pp. 642-656.

- — , "On Form, and the Possibility of Moral Beauty", Metaphilosophy 49:5 (2018b), pp. 711-729.

- — , "Functional Beauty, Pleasure, and Experience", Australasian Journal of Philosophy (2019a).

- — , "More Than Skin Deep", Aeon (2019b).

- Glenn Parsons and Allen Carlson, Functional Beauty (Oxford: OUP, 2008).

- Evelleen Richards, Darwin and the Making of Sexual Selection (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

- Roger Scruton, Beauty (Oxford: OUP, 2007).

- Paul C. Taylor, Black is Beautiful: A Philosophy of Black Aesthetics (London: Blackwell, 2016).

- Heather Widdows, Perfect Me! Beauty as an Ethical Ideal (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

This post is an expanded version from part of a draft for a Philosophy Compass article on beauty that Panos is currently working on.

Panos Paris is a Lecturer in Philosophy at Cardiff University and a Trustee of the British Society of Aesthetics. He works in value theory, and especially in the areas of aesthetics, ethics, and the intersection between them.