Authenticity and Make-believe in Competitive Games

Well, Euro 2020 has been and gone. Or rather it would have, had COVID-19 not swept it from the calendar along with all of humanity's non-banana-bread-baking hopes and dreams. Despite being 35 years old (yesterday was, incidentally my birthday), I would ordinarily be unable to contain my infantile excitement for the Euros. I have supported the country of my birth, Germany, since I was 6 when, alas, they faltered to Denmark (yes, you read that right) in the final of Euro '92 (in Sweden, no less!). I have 'fevered with' them, as you'd say in German, through the highs and lows (mostly highs, let's be honest), endured abuse from English schoolmates (envious, obviously), and risked physical violence to see them beat England live from the English stands. I have sobbed a handful of times as an adult: on my wedding day, at the births of each of my three children, and when Germany defeated Argentina to lift the World Cup in 2014.

And yet, with the competition postponed, life goes on more or less unperturbed. One may wonder why I or indeed anyone gets so invested in the fates of their favourite teams. After all, how Germany play has no direct bearing on how the rest of my life goes. And football, like other competitive games, is really quite arbitrary on its face: getting a ball into a goal seems a pretty meaningless exercise; doing so under stipulative restrictions (no hands!) seems less meaningful still. If pushed, many players and fans, of archery to Yahtzee, will concede that whether they win doesn't really matter. What's going on?

This is what I dubbed the 'Puzzle of Sport' in a 2017 paper published in JAAC. That paper took a look at the only direct attempt to solve the puzzle, Kendall Walton's 'It's Only a Game', criticized it, and offered an alternative. It has since come under criticism itself in a couple of papers, one by Nathan Wildman, another by Joseph G. Moore, both effectively Waltonians as regards competitive games.

I'll quickly describe Walton's solution to the puzzle, though I won't describe his expansive theory of fiction that the solution extends; the uninitiated should check out this summary. I'll then describe one of my criticisms and Wildman's response to it. Finally, I'll level the score by responding. This blogpost is pretty cavalier with subtleties and terminology; I encourage readers to check out the more meticulous papers on which it builds.

Walton and the Puzzle of Sport

Walton's contention is that often when we cheer and bewail our teams' (mis)fortunes, we are engaged in the same kind of activity as when we cheer on a hero in a film, or cry when a novel ends sadly: a game of make-believe. Events that are actually not very important (e.g. putting a ball in a goal; images on a screen manifesting certain appearances) make it fictional that there are outcomes that are very important. As sports fans, we therefore imagine that scoring a goal and winning the game matter immensely. The euphoria or disappointment we feel makes it fictional that we are overjoyed or devastated about the outcomes.

Walton's solution, if true, helps explain some at least apparent phenomena: our quick recoveries from sporting tragedies; the incongruity between our wild emotions during matches and our calm assessments soon after; our ability to support contestants on a whim; and the lack of indignation we (typically) feel towards others who don't support our team.

So far so good. However, there are problems for the account. I advance several of them in the 2017 paper in which I defend the view that, very roughly, our heightened interest in competitive game outcomes is ordinarily, contra Walton, genuine or literal rather than imagined or make-believe. The problem I will focus on here concerns what I call 'authenticity'.

Our heightened interest in competitive game outcomes is contingent upon players really trying. Where players feign effort, or play toward a prearranged outcome, spectator interest disappears or changes entirely. In the paper, I speculate that this may explain why 'sports' whose outcomes are known to be predetermined require heavy supplementation with other forms of entertainment. Pro wrestling's 'fights' are sustained by a background soap opera. The Harlem Globetrotters incorporate freakish feats of skill, pranks, and non-regulation props to sustain interest. This supplementation is much like the narrative that gives interest to fictional sporting encounters, such as the Rocky films. If authenticity is vital to our interest in the outcomes of competitive games but not standard games of make-believe, then this demands explanation. This amounts to a problem for Walton, I claim, because a very satisfactory explanation is that our interest in the outcomes of competitive, but not make-believe games, is genuine.

Dungeons & Dragons and Make-Believe

Wildman has criticized this argument by pointing to table-top role-playing games featuring dice-based resolution. Think Dungeons & Dragons. Such games ordinarily require that players not cheat with the dice on pain of spoiling the game (Wildman 2019, 269-270). Yet, standard fictions don't similarly require honesty. On this basis, Wildman runs a reductio on my argument: If the fact that playing sport but not traditional games of make-believe requires authenticity is reason to think playing sport doesn't involve make-believe, then the fact that playing D&D but not (other) traditional games of make-believe requires honesty is reason to think playing D&D doesn't involve make-believe. But this last implication is absurd, so we should reject the parallel line of argument in the case of authenticity, too.

I should note that the phrase 'involves make-believe' conceals an ambiguity that permeates Wildman's article. It could either mean:

-

(1) the game has some (even integral) make-believe components;

-

(2) our investment in the outcome of the game is make-believe.

My only interest is in denying claim 2. Claim 1 is uninteresting; competitive games involving make-believe, whether superficially (chess) or integrally (video games), abound. Indeed if, as is at least epistemically possible, a fictionalist analysis of norms and normative attitudes generally turns out to be true, then every competitive game will involve make-believe to some degree. But this is beside the point. So, for the reductio to work, it has to concern claim 2. So, now it's not enough to show that D&D involves make-believe components (claim 1), but that our investment in its outcomes is make-believe (claim 2).

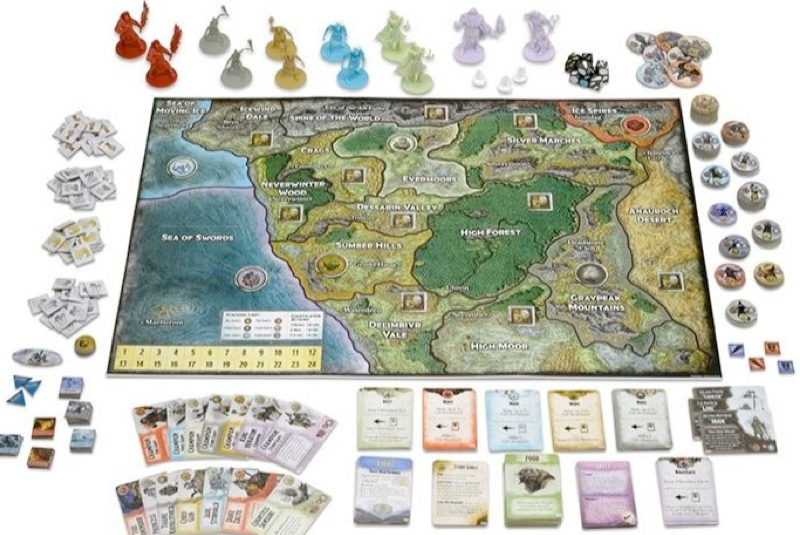

Dungeons & Dragons

Dungeons & Dragons

D&D is an interesting example because, unlike competitive games that clearly involve make-believe in sense 1 (e.g. competitive video games, Monopoly, etc.), D&D isn't straightforwardly competitive; there are no clear winners and losers as in badminton, say. This seems to preclude one possible rebuttal—namely, that the need for honesty in D&D is the result of a genuine, as opposed to make-believe, competitive interest—since there is no competition.

Yet, this is too quick: there are competitive elements to D&D, such as the accrual of Experience Points and the winning of battles. Arguably, it's precisely these elements for which honest dice are most important. And while the game is more cooperative than competitive, this cooperation often serves shared ends within the game, such as saving a town. These are competitive ends in my and Walton's sense, just as the ends in opponent-less, co-operative sports are, as when a team races against the clock. To be sure, the ends in D&D are probably integrally fictional like those in competitive video games: they aren't, and probably can't be, specified independently of the fictional world the game prescribes us to imagine. However, also like competitive video games, our interest in the game as competitors (whether make-believe or genuine) is in literally making certain things true according to the relevant fiction—for instance, to make it true according to the fiction that my character wins the battle, saves the town, etc.—even granting that our interests as players are much broader and involve imagined attitudes. So, one possible response to the reductio is that it actually reinforces my original argument rather than upending it: unusually for a make-believe game, honesty is required in D&D precisely because it is in relevant ways a competitive game after all.

While I think this is at least partly true of D&D, as a rebuttal to Wildman it is only a temporary fix. Other games with no meaningful competitive dimension have similar 'honesty' requirements. Improvised comedy, for instance, isn't competitive but requires (simplifying a little) that actors operate on the fly rather than to a script. A game in which a reader of a choose-your-own adventure commits to always choosing by coin-toss has a similar, if self-imposed, constraint.

The question is whether this just shows that 'different kinds of games of make-believe can have different pre-requisite conditions' (Wildman 2019, 269)—that is, different constraints on how the props work—which is undeniable. That would be a problem for my argument, according to which authenticity marks an important difference between our investment in the outcomes of competitive games and those of traditional fictions. If authenticity is just another constraint on how props can generate fictional truths, then the fact that we require sporting competitors to be authentic—to really try—shows much less than I claim.

However, again, I think this is too quick. I want to end by distinguishing two reasons why we insist on 'honest' props that vindicates my criticism of Walton. One reason is aesthetic: honesty makes realizing certain aesthetic values possible. Just as I might sculpt in a difficult medium, or exclusively improvise my comedy, or choose colours using a random number generator to achieve different effects or exercise different skills, so I may require that a fiction be generated with 'honesty' (e.g. by using coin tosses, audience prompts, etc.). A second reason concerns what I will call fairness: we demand honesty because without it, we don't know who really is the best or luckiest player or how well we did this time. For a situation to be fair in this sense is not for it to be equitable (a serious match between myself and Roger Federer is fair in this sense) but rather for it to take something like its natural course (i.e. Federer absolutely crushing me).

My tentative proposal is that in D&D, both of these reasons are in play. First, players care about working through a satisfying narrative in a way that isn't wholly within their control, since the objectivity of the dice adds spontaneity and unpredictability to the game. As Walton points out, much of the point of props beyond our deliberate thoughts, such as toys, is to enliven make-believe games with their independence and objectivity. These are aesthetic reasons to prefer honest dice. But, in addition, players also care about whether or not they will really win the battle, or how many Experience Points they will accrue based on how they play. These are fairness reasons for preferring honest dice.

If this is right, then my original criticism of Walton's view of sport still stands. For, we have a perfectly good explanation of why other kinds of make-believe games, like improvised comedy and coin-toss-choose-your-own-adventure have the constraints they do without being competitive games: the constraints allow aesthetic values to be realized. Insofar as I require the German football team not to play to a script, however, this isn't for aesthetic reasons (though I might have these too); it is for fairness reasons. My interest in their winning is premised on believing that when they win or lose, they really win or lose. If my distinction between these two kinds of authenticity works, then our investment in competitive game outcomes is constrained in a relatively unique way after all—one that is neatly explained by the genuine, rather than imagined, nature of that investment.

Bibliography

Stear, Nils-Hennes. 2017. "Sport, Make-Believe, and Volatile Attitudes." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 75 (3): 275-288.

Walton, Kendall L. 2015. ""It's Only a Game!": Sports as Fiction." In In Other Shoes, by Kendall L. Walton, 75-83. New York: Oxford university Press.

Wildman, Nathan. 2019. "Don't Stop Make-Believing." The Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 46 (2): 261-275.

Nils-Hennes Stear is a Visiting Research Fellow at Uppsala University and the University of Southampton, where he was, until recently, a Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellow directing the Art & Ethics project. Before this, Nils was a postdoctoral fellow at the Instituto de Investigaciones Filosóficas at UNAM. In August, 2020, he will begin as an instructor at the University of Auburn.