Aesthetics of action, arts of action

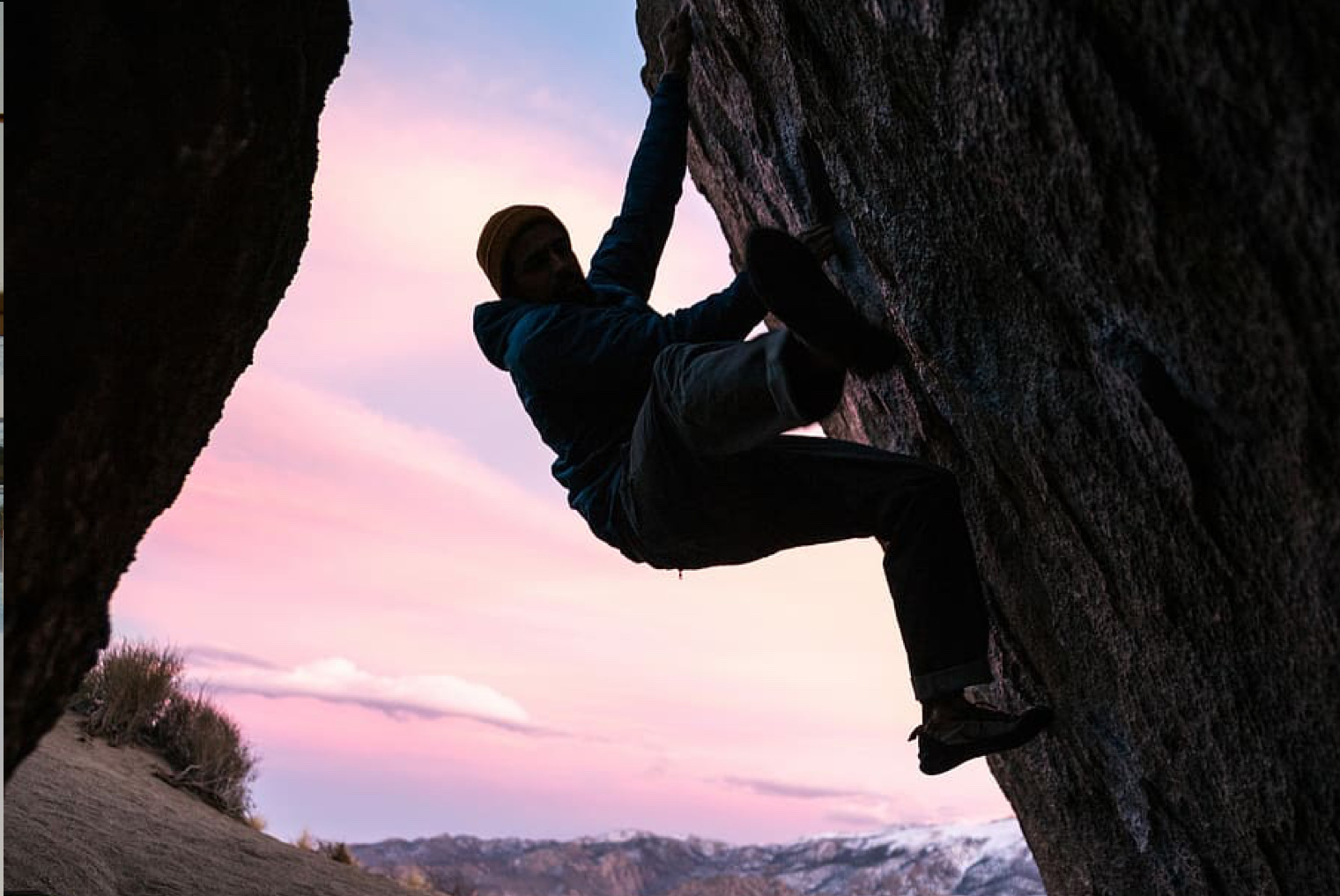

High art culture has tended to focus on the arts of objects and largely ignored the arts of action. These are the arts designed to call forth activity from their audience, for the sake of that audience’s appreciation of their own activity. I mean things like: rock climbing, games, improvised communal dance, and social food rituals. These arts are either marginalized by high art culture, or they are awkwardly squeezed to fit into the paradigm of the object arts.

We make all sorts of things for aesthetic purposes. Let’s call these the practices of the “arts”, for now. But there are two very different categories of arts. And our theories and critical apparatus have all been built to cope with the arts of objects. In the arts of objects, an artist makes a thing, and we are supposed to appreciate that thing itself. But the arts of action involve a more distant — and more participatory — relationship between the artist, and what the audience is supposed to appreciate. In the arts of action, an artist makes a thing, and then the audience is supposed to interact with the thing, to let it call forth and sculpt their actions. And then the audience is supposed to appreciate their actions — their own choices, movements, and struggles.

For example: rock climbing is a profoundly aesthetic sport — but the center of the rock climbing aesthetics has always been the rock climber’s appreciation of their own movement. Rock climbers are always talking about how a particular climb brings out a delicate, beautiful movement, or a thrilling, explosive leap. Social tango dancers, too, dance for their own feeling of improvisation and connection. We’re talking about the real tango here — the improvised, communal tango — and not the choreographed tango of the stage. Beatriz Dujovne describes the experience of the social tango dancer:

They improvise. They dance for themselves, introspectively. Shunning the external world, their eyes turn inward. This circumspect dance comes from a different heart and culture than the stage dance… At social dances we see neither sexual passion nor violence. The dance’s form is different as well. Legwork is minimal; feet are kept on the floor; the size of the steps is small. People dance closely embraced to one another, bodies connecting, chests close together, heaving and retreating with every breath, heads resting delicately together, moving as one, immersed in total improvisation that forbids them to hide behind choreographed steps. Beauty radiates from the emotions inside the dancers, not from external displays of skill.

These sorts of aesthetic experiences aren’t confined to designed art practices. Our ordinary life is chock-full of aesthetic experiences of our own thoughts and actions. A box falls into the road; we dodge it with a graceful swerve. The structure of our argument eludes us, and then everything falls into place with a moment of shining epiphany. We cannot fit all this furniture into this tiny van, but then we figure out just the right way to interlock the various protrusions.

But, importantly, these aesthetic experiences of one’s own actions can also be evoked by designed objects. This is why I call it an art, rather than just an aesthetic appreciation in the wild. The social tango is a practice with evolved rules and norms and techniques, all designed to call forth the beauty of subtle improvised coordination. John Dewey said that the arts take bits of our natural, everyday practical experience and crystallize them. Painting crystallizes seeing; fiction crystallizes everyday narration. The same is true with the arts of action. Boxing crystallizes the joys of dodging and weaving; chess crystallizes the joys of logical epiphany; social tango crystallizes the joys of intimate coordination; and Tetris crystallizes the joys of, well, Tetrising shit.

The aesthetics of action are thus not, as has been sometimes suggested, merely a matter of everyday aesthetics. In her influential discussion of everyday aesthetics, Yuriko Saito suggests that the aesthetics of action are essentially opposed to the practices of art. The practices of art, says Saito, are about stabilizing aesthetic experiences around carefully delineated objects. Art involves frames, both physical and mental. These frames focus our attention along communal tracks. We are supposed to attend to what is in the frame of the painting and ignore its relationship to what is outside. And we are supposed to attend to the visuals of a painting, but not how the paint tastes or smells. This works with traditional art objects, because the audiences are so passive, and the objects so stable, says Saito. But the aesthetics of actions, says Saito, are too active and variable and unruly. They cannot be captured in an artifact, or corralled with norms of proper observation. In my language, Saito is saying that there can be no arts of action.

But, in actuality, we do create artifacts for the sake of sculpting the aesthetics of action. And there are all sorts of normative framing practices associated with those artifacts. The examples are everywhere; we have simply overlooked them, perhaps because of the narrowness of our theory of art. Games provide a perfectly clear example of the practice. They are designed objects, and they are framed with prescriptions about how we should approach them and appreciate them. The normative frame around a game can be seen in its breach. There are right and wrong ways to attend to games. Imagine, for example, reviewing a videogame after smelling the disc, or after only listening to the theme music on the title screen. Games are carefully designed to offer us semi-stable experiences of our own beautiful activity, and that requires that we approach and interact with the designed object in certain, communally designated ways. Game designers manipulate rules and environments and agencies to provide their players with very specific, aesthetically rich experiences of their own practicality and activity. And to get at those designed aesthetic experiences, we must follow certain norms, playing games by their rules and trying to reach the prescribed goals — just like we need to look at a painting from the front, and read the words of a novel in order. These rules bring us into closer reach of sharing particular designed experiences.

Here’s a theory of the arts of action — or as I sometimes call them, the “process arts”. In the traditional object arts, the artist makes an artifact, and the audience is supposed to appreciate the artifact itself. In the process arts, the artist makes an artifact, and then the audience interacts with the artifact. The artifact is designed to evoke a particular kind of activity from the audience, and then the audience is supposed to appreciate their own activity. Or, to put it another way: in the object arts, the aesthetic properties are contained in the stable artifact. It is the book that is dramatic, the poem that is gorgeously cryptic. In the object arts, we might say, the artist transmits a certain aesthetic quality to the audience by placing it in the work itself. But in the process arts, the aesthetic properties emerge in the audience’s activity, as it is evoked by the stable artifact. It is the tango dancer whose movement is elegant, refined, and intimate — and those qualities are primarily accessible to the dancer themselves. But the rules and traditions of tango help call forth and shape the particular aesthetic joys of tango.

To make this clearer, let’s distinguish between two things that are often blurred: the artist’s work and the appreciative focus. The artist’s work is the stable object an artist makes and passes to their audience. The appreciative focus is whatever it is that the audience is supposed to attend to. The distinction between artist’s work and appreciative focus has not been properly appreciated, because in the object arts, they are usually identical. The artist writes the novel, and we appreciate the novel itself. But in the process arts, they come apart. The artist is more distant from their aesthetic effects; they must achieve their aesthetic goals through the free agency of their audience.

But I think much of the time, when we are confronted with a process art, we try to force it into an object art paradigm, and that forces our attention down the wrong track. For example, much of the attempt to show that games are a serious and respectable art form has focused on praising the stable features that fit most neatly into an object-art paradigm. Scholars of aesthetics — and other defenders of games — have, in their quest to show that games are art, focused on aspects of script, narrative, graphics, or how the game’s rules model and represent systems in the real world. Theorists have often neglected games’ special ability to shape our choices and actions in an aesthetically rich way — even though these features are most central in the natural aesthetic talk of game-players and game designers.

Also, many of our art practices are, I think, hybrids, with both object and process art qualities. But we often elide their process art qualities and focus narrowly on their object art qualities when we try to bring them into our critical view. Take, for example, cookbooks. Cookbooks offer us some object art qualities — in the writing, the pictures, and the food we produce. But they also offer us process art qualities. Cookbooks shape our cooking actions. They can make the cooking process elegant — full of rich aesthetic attention to ingredients sizzling, and graceful actions. Or they can make the process ugly, clunky, and desperate. But notice that when we review cookbooks, we by and large ignore the process and qualities, and focus entirely on the object qualities. Why? So much of the time, the majority of our interaction with a cookbook is in the cooking itself — and that process is one that is carefully designed, and a core part of the actual content of the book itself. The answer, I suggest, is that our theory of the arts has elided the process arts — which drives our attention away from much of the aesthetic richness available to us.

Finally, who has aesthetic responsibility here? Is it the artifact-maker or the audience? For the answer, I suggest we draw from Nick Zangwill’s theory of aesthetic responsibility. According to Zangwill, the person with aesthetic responsibility — the artist — is the person who intentionally arranges non-aesthetic properties to create an aesthetic effect. The painter puts this bit of paint here and that bit of paint there, in order to create a graceful line, or a brooding feel.

Who, then, is the artist in the process arts — the designer, or the audience? The answer will vary enormously from one process art to another. In the social tango, I suspect that most of the aesthetic responsibility lies, not with the designer of the practice, but with the individual dancers themselves. It is the dancers who know that moving like so will create a sensuous sense of graceful connection. But with games, it is often the artifact-maker. It is the game designer who manipulates rules and goals, who manipulates virtual environment and virtual physics, in order to give the player a particular sense of thrill and grace from their struggle. Much of the time, the player doesn’t have aesthetic effects in mind. They are just trying to win. But their attempts to win are guided along carefully pre-arranged courses, by the designer’s manipulation of the affordances and environments of the game-world — and those manipulations can call forth beautiful, graceful actions.

This blog post is a summary of ‘The Arts of Action’ (Philosopher’s Imprint). The full version contains a lot more of the technical nitty gritty, as well as an attempt to diagnose Western art culture’s marginalization of the process arts.

C. Thi Nguyen used to be a food writer and now is a philosophy professor in Utah, writing about trust, art, games, and communities. Read more about his work on his website.